TL;DR: Epistemic debt is what happens when you ship code you can’t explain. AI creates an illusion of competence: code that looks professional, tests that pass, but without the understanding you need to debug, extend, or defend it later.

“Write code faster”. Managers see cycle time. Developers are divided. Some see glorified autocomplete; others see “amateur hour”. I’m in the camp that sees the beginning of engineers as leaders: less time typing code, more time defining intent and managing risk - and if you generate 1,000 lines of code in a few seconds, you have not just solved a problem, you have created a maintenance obligation.

AI is part of my everyday workflow now. At its best, it scales my work: it can pick up a half-finished thread after a week away, and it gives me a kind of semantic map of a codebase.

Not “search” as in grep. More like: trace how concept X flows through the system, show me every call site that can trigger behaviour Y, where is this validated / transformed / logged, and what else would a change here plausibly break. Questions like that used to take a ticket and a block of time. Now it’s seconds.

And separately: it turns ideas into something I can look at. For me as an (aphant), that externalising step is a super productivity boost.

At its worst, it is confidently wrong in ways that look tidy. I spend a lot of time steering it away from dodgy abstractions and subtle breakage. I’m able to spot that because I’ve made those mistakes myself.

I have written before about the economic and environmental costs of the infrastructure itself. But the other bill, the one your team pays directly, arrives as review time, churn, and security flaws.

The defining challenge: epistemic debt

Epistemic debt is what happens when you ship code you can’t explain. Not technical debt from shortcuts - this is the illusion of competence. Code that looks professional, tests that pass, but without the understanding to maintain it.

I have caught myself here. Deep in the flow, the model starts doing more than filling in syntax: it begins choosing the shape of the solution. You still feel like you are “writing code” because you’re nudging and iterating, but your role has quietly shifted from driving to supervising.

The danger is not that you’re rubber-stamping. It’s that the handover of control is gradual enough that you only notice later - when you need to explain the change or debug a weird edge case, and you realise you haven’t built the mental model.

If you can’t explain it, you didn’t ship a solution - you shipped a mystery.

Bugs happen in hand-written code too. The difference is recovery cost. When you write the change, you usually build a mental model as you go: what it assumes, what it touches, and where it is fragile.

With AI, the work shifts. You become the reviewer of a draft you did not author. That can be fine, but only if someone still does the ‘authoring work’ - internalising the change.

Shipping code is taking responsibility for its behaviour. If you can’t explain what a change does, what it assumes, and how it can fail, you don’t really own it. AI doesn’t remove that obligation - it increases the amount of code you can produce, which makes the ownership requirement more important, not less.

Why epistemic debt amplifies every other risk

Epistemic debt matters because when you don’t understand what you’ve shipped, you can’t spot problems lurking beneath the surface. It makes every traditional software risk worse:

1. The churn

GitClear’s AI code quality research looks at real codebase change patterns rather than anecdotes. Their headline signal is a shift in how code changes happen.

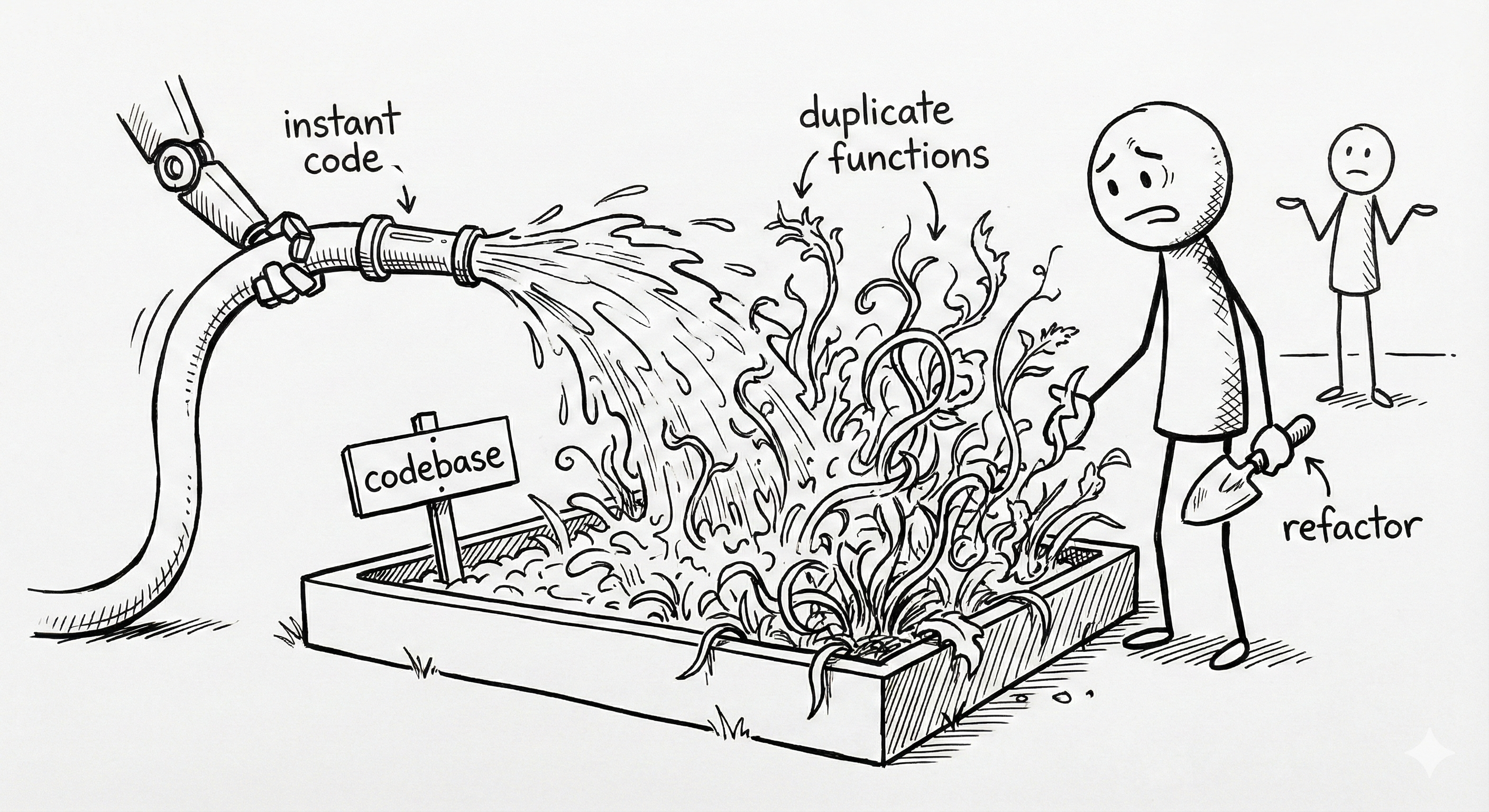

They found that “moved” code is down (often a proxy for refactoring), while copy/paste changes are up (duplicate logic - no respect for the rule of three).

The problem, is the path of least resistance. It’s easier to ask a model to “add a function that does X” (append-only) than to ask it to “refactor the existing class to support X generically” (edit-in-place). Without strict guidance, the default outcome is a codebase that grows faster than it improves.

Why epistemic debt makes this worse: If you don’t deeply understand the change, you won’t recognize when you’re duplicating existing logic. The AI draft looks reasonable, tests pass, so you merge it - never realizing you just created the third variation of the same pattern.

What this costs in practice: duplicated logic, inconsistent behaviour, and more code to maintain. This is something I have seen firsthand.

2. You can’t catch the security flaw

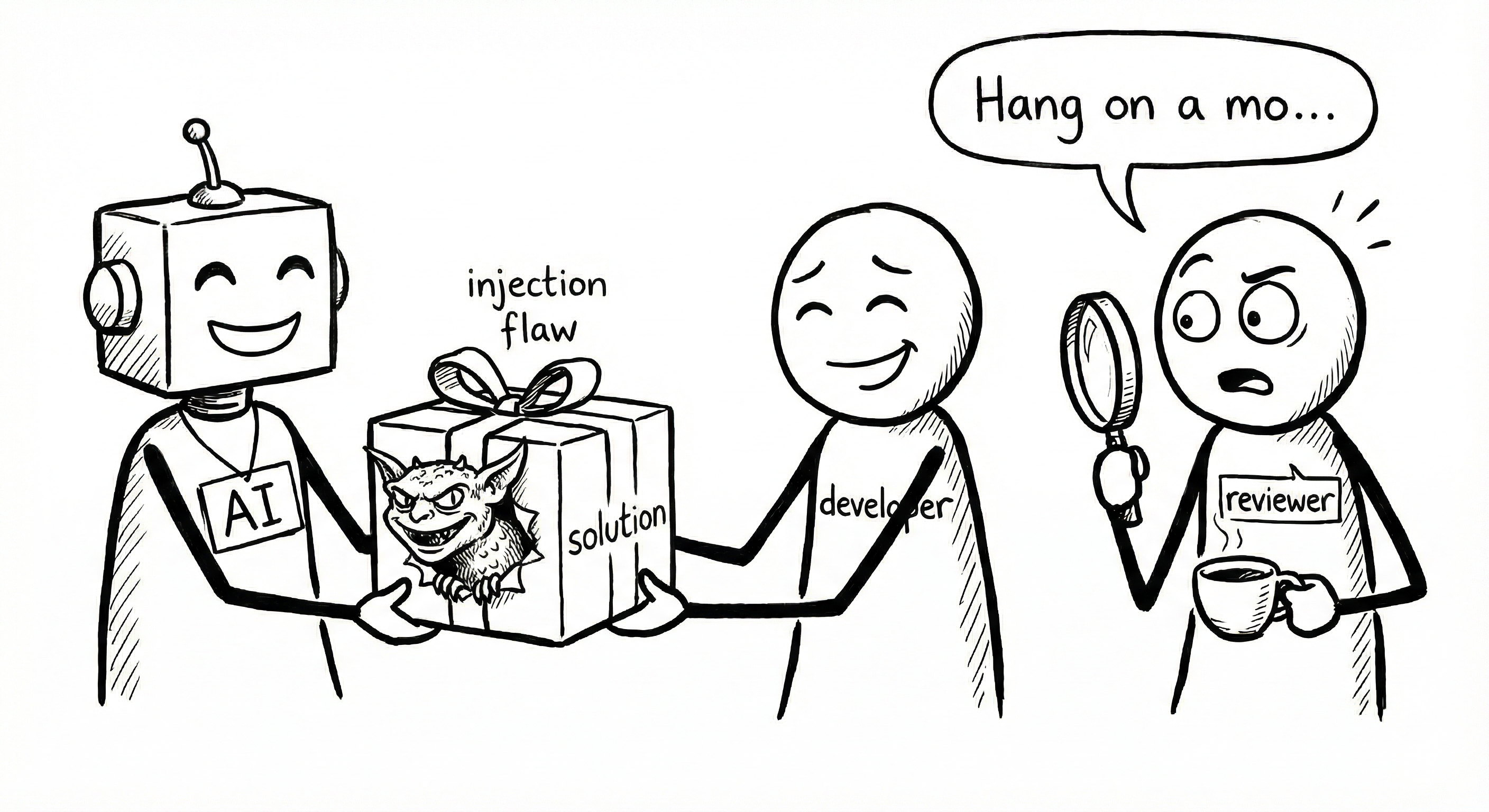

Models are getting better at security. But the research highlights a human problem, not a machine problem: overconfidence.

Because the code arrives formatted, commented, and syntactically perfect, our brains lower their guard. We assume competence in syntax equals competence in logic.

Why epistemic debt makes this worse: It is not always a blatant injection flaw. It is often a subtle logic assumption that looks reasonable in review, passes tests, then fails in production because the real world violates an unstated precondition. If you don’t understand the implementation deeply, you won’t spot the hidden assumption.

What this costs in practice: Security incidents and production failures that could have been caught in review - if the author or reviewer had built a proper mental model of how the code actually works.

3. You can’t diagnose stability issues

DORA’s reporting captures something many teams are feeling: AI can lift individual throughput, while trust, coordination, and stability become the limiting factors.

My shorthand for this is the vacuum hypothesis:

Time saved on authoring is vacuumed up by review, debugging, coordination, and operational work.

Why epistemic debt makes this worse: When something breaks in production, the person who wrote the code can’t explain how it was supposed to work. The team has to reverse-engineer intent from the diff, logs, and history - paying twice to understand what should have been understood before merge.

That is not an argument against AI. It is an argument against treating it as free speed.

Opting out is not realistic

Even if you accept every risk above, I don’t believe that a full opt-out is viable. Some work genuinely becomes cheaper, especially scaffolding and first drafts - and if you refuse that leverage entirely, someone else will ship faster.

This is the uncomfortable part: if AI gives even a 20% advantage in certain loops, the teams that take it will deliver features faster, and markets will reward them. The market does not care if your code was artisanally hand-crafted, if you ship six months late.

So the question is not “AI or no AI”. It is “what operating model prevents AI from turning speed into debt”.

Where epistemic debt shows up in teams

- LGTM in good faith: the reviewer wants to review properly, but the author cannot explain intent, assumptions, or failure modes. Review degrades into “tests pass and it looks tidy”.

- Silent contracts: the implementation bakes in an unstated assumption (ordering, nullability, idempotency, tenancy, time zones). The tests mirror the assumption, so nothing fails until production violates it.

- Dependency drift timebomb: AI pulls in a library or pattern that is slightly off your ecosystem (licensing posture, security posture, operational footprint). Months later you hit a vulnerability advisory or an upgrade break, and nobody can answer why it is there.

One caveat: decent models do now produce good comments and a neat explanation of what they did. That helps. But comments are not comprehension. The debt is paid down only when a human can explain the change, including what it assumes and how it can fail.

The review bottleneck: 10 seconds to generate, 10 minutes to review

AI changes the shape of the pipeline:

- Drafting got a lot cheaper.

- Review, validation, and operational confidence did not.

This is where “LGTM syndrome” comes from. Reviewers are asked to absorb more change than attention allows, so they start pattern-matching for obvious issues and miss deeper problems: intent mismatches, edge cases, and system impact.

The solution is to embrace, but validate

This is the pivot: the total cost of AI is only high if you treat it as magic.

The analogy I keep coming back to is aviation. Modern systems can automate an enormous amount of the routine work, and they do it with superhuman consistency.

But the operating model still assumes a pilot in control of aircraft: someone who understands what the system is trying to do, monitors for when reality diverges from the model, and takes over when it matters. The risk is not that the automation is stupid - it’s that it is good enough to lull you into not noticing when you’re no longer fully in control.

Capability is not the same thing as responsibility.

Treat AI like a junior engineer: fast, useful, sometimes brilliant, often overconfident, and in need of constraints and checks.

Shift the mindset from “write code” to “own intent”

If you use AI as autocomplete, you get faster typing.

If you use AI as an agent, you can move faster without losing intent, but only if you add guardrails.

I wrote about this in Autocomplete Was Never the Point: I believe the true the leverage is delegation, not predictive completion.

The bottom line

The illusion of competence is the real risk. AI produces code that looks professional, tests that pass, diffs that seem reasonable - but without the understanding you need to maintain it.

If you treat AI as free speed, you will pay interest later in churn, security incidents, slower reviews, and epistemic debt: working code that nobody on the team can fully explain.

If you treat AI as a fast intern, and invest in solid specs, tests, and validation gates, you can keep the speed without bankrupting the codebase.

Use AI. Get good at it. But keep your hands on the wheel. If you can’t explain the change in plain language, it isn’t speed - it’s epistemic debt, and the bill will arrive when you least expect it.

Sources

- GitClear: Coding on Copilot (AI code quality research) - change-pattern analysis (code movement vs copy/paste signals)

- DORA: Accelerate State of DevOps Report 2024 - delivery performance framing, with notes on generative AI and outcomes

- Your AI Coding Assistant Is Quietly Creating a New Kind of Technical Debt - Stanislav Komarovsky, Medium (2025)

- The Illusion of Competence: Defining ‘Epistemic Debt’ in the Era of LLM-Assisted Software Engineering - Ludovic Ngabang, viXra (2026)

- Epistemic Debt: A Concept and Measure of Technical Ignorance - Ionescu et al. (2019) (The original academic definition in manufacturing)

- Do Users Write More Insecure Code with AI Assistants? - Perry et al., arXiv (Stanford/Cornell), 2022

- Assessing the Security of GitHub Copilot’s Generated Code - Majdinasab et al., arXiv, 2023 (replicating and extending Copilot security analyses)

- DORA: State of AI-assisted Software Development (2025) - DORA research on how AI interacts with software delivery outcomes

Comments