Each interaction with an AI coding assistant carries costs that are not reflected in the subscription price. AI companies are losing billions of dollars while consuming vast amounts of energy and water. Understanding these hidden costs matters for developers making informed choices about how deeply they integrate these tools into their work.

The Financial Reality Is Investor Subsidies

OpenAI

OpenAI’s financial position in September 2024, according to reporting by the New York Times:

- Monthly revenue: $300 million (August 2024)

- Projected 2024 revenue: $3.7 billion

- Estimated 2024 losses: approximately $5 billion

- Revenue growth: 1,700% since early 2023

- Funding raised: approximately $7 billion at a $150 billion valuation (reported across multiple outlets, October 2024)

That equates to roughly $1.35 lost for every $1 earned. The revenue does not cover the compute, infrastructure, research, and staffing costs required to operate frontier models at scale.

Anthropic

Anthropic’s growth follows a similar pattern. Public disclosures through 2024 show rapid enterprise adoption and aggressive fundraising, including multi-billion-dollar rounds led by strategic partners.

The company does not publish detailed profit and loss figures, but the scale and pace of investment strongly suggest ongoing operating losses as it prioritises growth, capacity, and model development over near-term profitability.

What Does This Mean for Pricing?

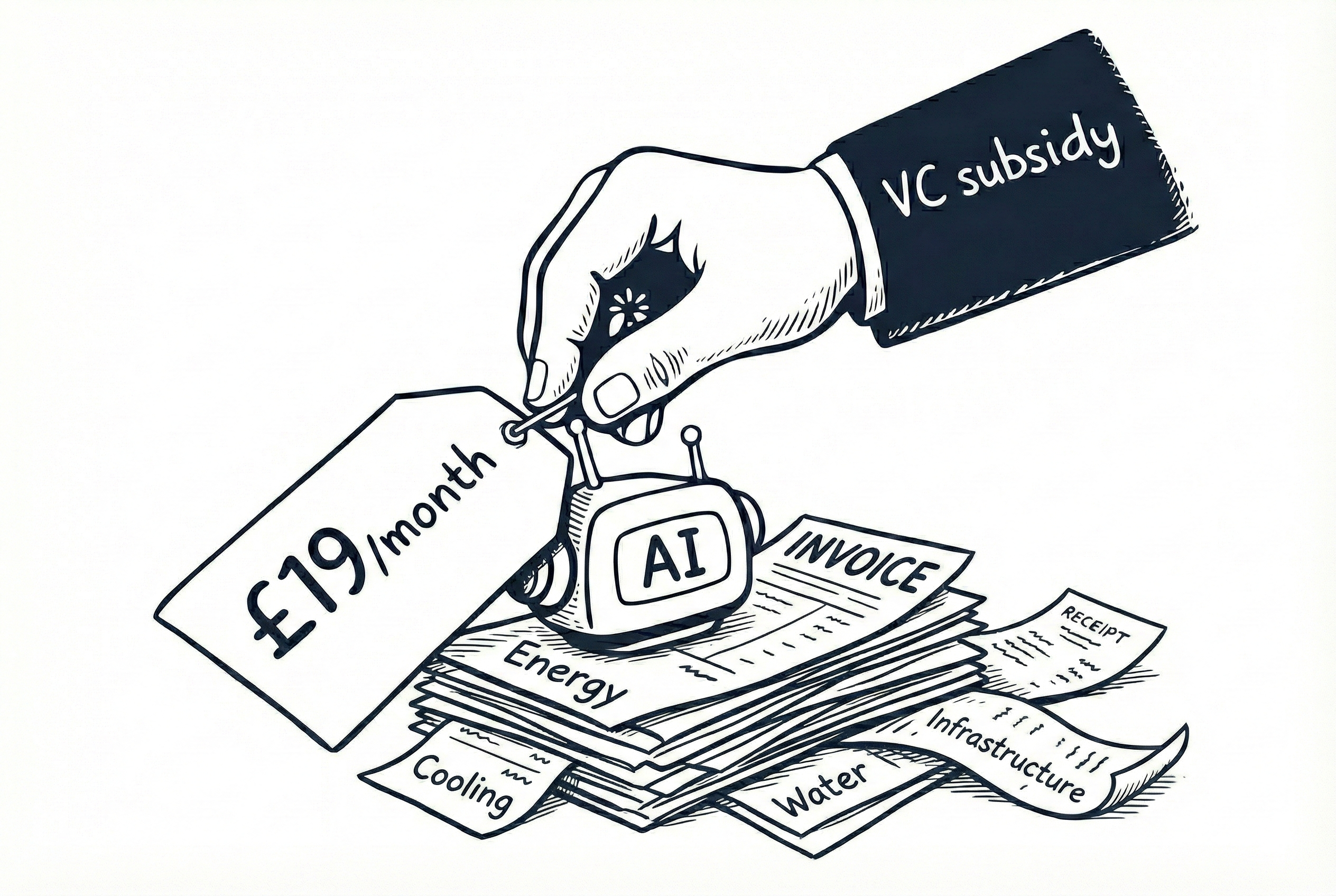

The prices developers see today, whether Copilot at £19 per month or Claude Pro at £17 per month when billed annually, are almost certainly below the true cost of delivery.

The pattern is familiar:

- Subsidise usage to acquire users

- Build habits, workflows, and switching costs

- Raise prices once market position stabilises

We saw this with Uber. Early pricing felt implausibly cheap. It was. Once subsidies receded, prices adjusted to economic reality.

API Pricing: A Subsidised Race

API pricing makes this dynamic clearer. In 2023, a typical GPT-4 coding task (around 50K input and 10K output tokens) could cost roughly $2.00. By late 2025, comparable tasks are far cheaper.

| Model (late 2025) | Approx. $/task | vs GPT-4 (2023) |

|---|---|---|

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | $0.30 | ~6.7× cheaper |

| GPT-4.1 mini | $0.03 | ~67× cheaper |

| Gemini 2.5 Flash | $0.04 | ~50× cheaper |

These figures are illustrative rather than exact equivalence, but the trend is clear.

Has efficiency really improved fifty to sixty-seven times in two years? Possibly. But providers are also competing aggressively on price, with investors absorbing much of the cost. No one wants to lose ground during a land grab.

Won’t Efficiency Fix This?

Improving efficiency absolutely helps, and it is happening. But lower cost per request does not automatically mean lower total cost.

As inference becomes cheaper, it becomes easier to justify using AI more often, in more places, by more people. Features that once felt extravagant become default. Background agents appear. Always-on assistance creeps in. Total system load rises faster than unit costs fall.

Developers have seen this pattern before. Cheaper resources change behaviour. Unless usage is deliberately constrained, efficiency gains tend to increase demand rather than cap it.

The Environmental Cost (for Developers)

From a software development perspective, AI usage behaves less like running a compiler and more like making a remote call to a large, continuously operating data centre. The cost is externalised, but it is still real.

Every prompt triggers compute across clusters of GPUs, backed by power delivery, cooling, redundancy, and networking. The abstraction is clean. The system underneath is not.

Energy Consumption

The exact energy cost per prompt is not public, but the direction of travel is clear.

We often fixate on the training costs—the massive energy spike required to build a model. While those numbers are huge (Strubell et al. showed way back in 2019 that training one model could emit as much CO₂ as five cars), they are essentially a one-off ‘capital expenditure’.

The real, ongoing cost is inference.

This is the energy used every time the model answers a question. Unlike training, which ends once the model is released, inference runs 24/7. Every time you hit Tab or ask for a refactor, you aren’t retrieving a cached file; you are triggering a fresh, complex calculation on a GPU. It scales linearly with every user. It’s the difference between the energy to build a car and the fuel needed to drive it every day.

The International Energy Agency’s Electricity Report 2024 projects that global data centre electricity demand will roughly double by 2026. AI workloads are a primary driver. In some regions, additional demand is being met by keeping older fossil-fuel plants online rather than by new renewable capacity.

From a systems point of view, this is a classic scaling problem: latency and reliability expectations increase faster than clean energy supply can adapt.

Water and Cooling

Compute density creates heat. Heat must be removed.

Large data centres rely heavily on water-intensive cooling, particularly in warm or water-stressed regions. Microsoft’s 2025 Sustainability Report highlights that newer direct-to-chip cooling systems can save over 125 million litres of water per facility each year.

That figure is useful precisely because it implies how much water traditional cooling consumes.

For engineers, the key point is that cooling is not an optimisation detail. It is a hard constraint that determines rack density, data centre placement, and how fast AI infrastructure can scale at all.

Carbon Offsets Are a Lagging Fix

Major providers have made serious sustainability commitments:

- Microsoft aims to be carbon negative by 2030

- Google targets 24/7 carbon-free energy by 2030

These programmes involve real investment and real progress. They also exist because current operations generate a substantial footprint.

Offsets and renewable contracts operate at organisational timescales. Inference demand grows at product timescales. The gap between the two is where environmental cost accumulates.

What Should Developers Do?

1. Factor in Future Pricing

Assume today’s prices are temporary.

Ask yourself:

- What productivity gains are you actually seeing?

- Could your workflow survive if prices doubled?

- Are you building dependencies that would be painful to unwind?

2. Match the Model to the Task

Using a large reasoning model for trivial completions is like driving a lorry to pick up groceries.

In practice:

- Smaller models for autocomplete and boilerplate

- Mid-tier models for everyday development

- Top-tier models only for genuinely complex reasoning and large code reviews

This is a cost decision and an efficiency decision.

See my quick picks to match model to task. Updated monthly.

3. Consider Local Models

For high-volume work or privacy-sensitive code, local models can be compelling. Tools such as Qwen 2.5 Coder (32B) achieve strong coding benchmarks with zero per-query cost once running.

See my article on the current state of local coding AI models.

4. Stay Informed

AI pricing and capabilities will keep changing. What is subsidised today may not be tomorrow.

Personally, I am finding Copilot’s pricing multipliers and broad model selection useful, because they make cost explicit at the point of use, directly inside my IDE.

The Bottom Line

AI coding tools are remarkable, and remarkably subsidised.

OpenAI’s multi-billion-dollar annual losses and Anthropic’s aggressive fundraising are not a stable end state. Even with continued efficiency gains, always-on inference at scale will not be free.

At some point, the system must rebalance through some combination of:

- Further efficiency gains

- Higher prices or stricter usage limits

- Consolidation as weaker players exit

None of this means developers should avoid AI tools. They offer real value today. But understanding the true costs helps you decide how deeply to depend on them.

The electricity powering your prompts, the water cooling the data centres, the billions of investor dollars underwriting each response: those are the real costs of AI. Today, you are not paying them directly. But someone is.

Sources

- New York Times, “OpenAI Is Growing Fast and Burning Through Piles of Money” (September 2024)

- Anthropic public fundraising disclosures (2023–2024)

- Microsoft Environmental Sustainability Report 2025

- IEA Electricity Report 2024

- Strubell, Ganesh, McCallum, “Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP” (ACL 2019)

- Google Sustainability Reports

Comments