TL;DR: AI can produce a lot, quickly. The job is keeping it coherent: what are we changing, why, what breaks, how do we know, and how do we roll it out. Delegation is the win; responsibility doesn’t go away.

I’m talking about tools like ChatGPT and GitHub Copilot used as delegated, parallel workers, not just autocomplete.

Autocomplete - “Intellisense on crack”

The version of AI I’m not excited about is predictive autocomplete that confidently guesses whole functions, control flow, or behaviour from a few lines of context.

When I’m choosing to do the coding myself, I want to think: shape the solution deliberately, reason about constraints, edge cases, and failure modes. Having an LLM jump ahead and guess my intent often interrupts that process more than it helps.

I am a fan of mechanical shortcuts. What I don’t want is intent guessed for me.

It was initially how AI-assisted coding was framed - less boilerplate and smarter in-editor suggestions. The problem is that this framing has lingered, and it obscures where the leverage actually is now.

Code review as an example

I’m seeing the same sales pitch around code review: treat review as a throughput problem, then sell AI as the fix.

That’s risky, because review is one of the places we most need human attention. It’s where we check intent and system impact: what are we changing, why, what could break, and what does this do to everything around it.

If a draft was generated in seconds, review can accidentally become the first time a human brain really processes the change. That is a massive shift in responsibility, and it’s not a shift you want by default.

I do use AI to assist code reviews, but more for broad coverage, like automated tests or static analysis. It catches obvious issues and asks awkward questions early, so I can spend time on the high-value part. Even here, model choice matters: fast models for surface-level checks; stronger reasoning models when I want it to challenge risk and trade-offs. (See my quick picks.)

AI-in-review has to be intentional.

I’ll pull the diff down, ask targeted questions, and treat it as one of the steps in my review. Always-on analysis in a PR risks becoming ambient noise. I want AI to sharpen attention, not dilute it.

The mode that actually changed how I work

For the moment, we’ve settled into a different shape of collaboration with AI, and it is not autocomplete. It is agentic chat: chat, plus delegated tasks that can read code, suggest edits across files, run checks, and iterate.

Instead, delegation: working the way I already work with a team, just faster and more parallel. Delegation also requires more discipline than doing it yourself.

This feels natural if your day already involves coordinating work, managing risk, and holding the system in your head, rather than staying deep in one implementation thread.

On non-trivial work there are always multiple threads: explore an approach, test assumptions, read docs, check edge cases, and do setup/testing. Agentic AI lets me run those threads in parallel. I’ll put one agent on a migration strategy, another on a data model, another on a library I don’t fully trust yet. I question the answers, push back, redirect, discard a lot, and I’m still the one steering: scope, priorities, and what “done” means.

That doesn’t feel like automation. It feels like leadership.

Why this feels familiar to experienced engineers

Agentic AI clicked for me quickly because it doesn’t require a new way of thinking about engineering.

Many of the practices we rely on now, exist to reduce risk, not maximise speed: pairing, design review, parallelising work, challenging assumptions. Agentic AI fits into this perfectly.

Double down on what good teams already do

This is why the joking around “AI-assisted juniors” misses the point. When code is cheap, unclear intent is expensive, and you feel it faster. The answer isn’t to reject the tool. It’s to double down on what good teams already do: strong review, explicit assumptions, and real ownership.

Agentic AI makes it much faster to try ideas, but it does not remove the need to do the work engineers have always done: understanding requirements, thinking through design, checking assumptions, and considering system impact.

Experience compounds here. The hard part was never typing code. It was knowing what mattered, what could go wrong, and where to be careful.

Where things actually go wrong

What I’m seeing in on the ground now is not about seniority. It is about mode selection.

- Overuse without discipline: the AI does good local work, but the developer stops leading the system. Scope, constraints, and checks aren’t made explicit.

- Underuse out of principle: treating failure as proof it has no place in serious work. We wouldn’t judge a human collaborator this way.

- Confusion about responsibility: oscillating between over-trust and total dismissal, because no one has a clear model for what humans must still own.

The elephant in the room - our future as devs

In the very long term, if the rate of improvement continues, it’s reasonable to ask whether we still need as many developers in the trenches 😢

But my bigger concern is messy middle phase: the months/years (maybe longer) where the tools are powerful enough to create a convincing demo, but not reliable enough to run a business-critical system without human engineering behind it.

This is also where the incentives get weird. If AI makes it look like software is now “just prompts”, some organisations will try to route feature delivery around engineering: PMs, analysts, or vendor teams driving changes directly.

We’ve seen this movie before in waves of “we don’t need developers”: low-code/no-code platforms, heavily outsourced feature teams, third-party “service accelerators”. The pitch is always the same: the business can move faster without waiting for engineers.

The outcome is often the same too:

- It works for simple cases, then hits hard limits (it can’t do X or Y).

- The platform/support burden is underestimated (observability, security, upgrades, incident response, data migrations). Or overlooked completely and it just gets handed over to the Platform team with no warning!

- The best developers leave or refuse to touch it because it feels like downskilling.

- The remaining work becomes mostly glue code and escape hatches, until you end up with a Franken-system: part platform, part bespoke, hard to change, and hard to reason about.

That’s why I’m pushing the “delegation” framing for now. If you treat AI like a shortcut around engineering, you get fragile systems. If you treat it as a force-multiplier inside engineering, you can get real speed without losing ownership of intent.

Where the real cost shows up

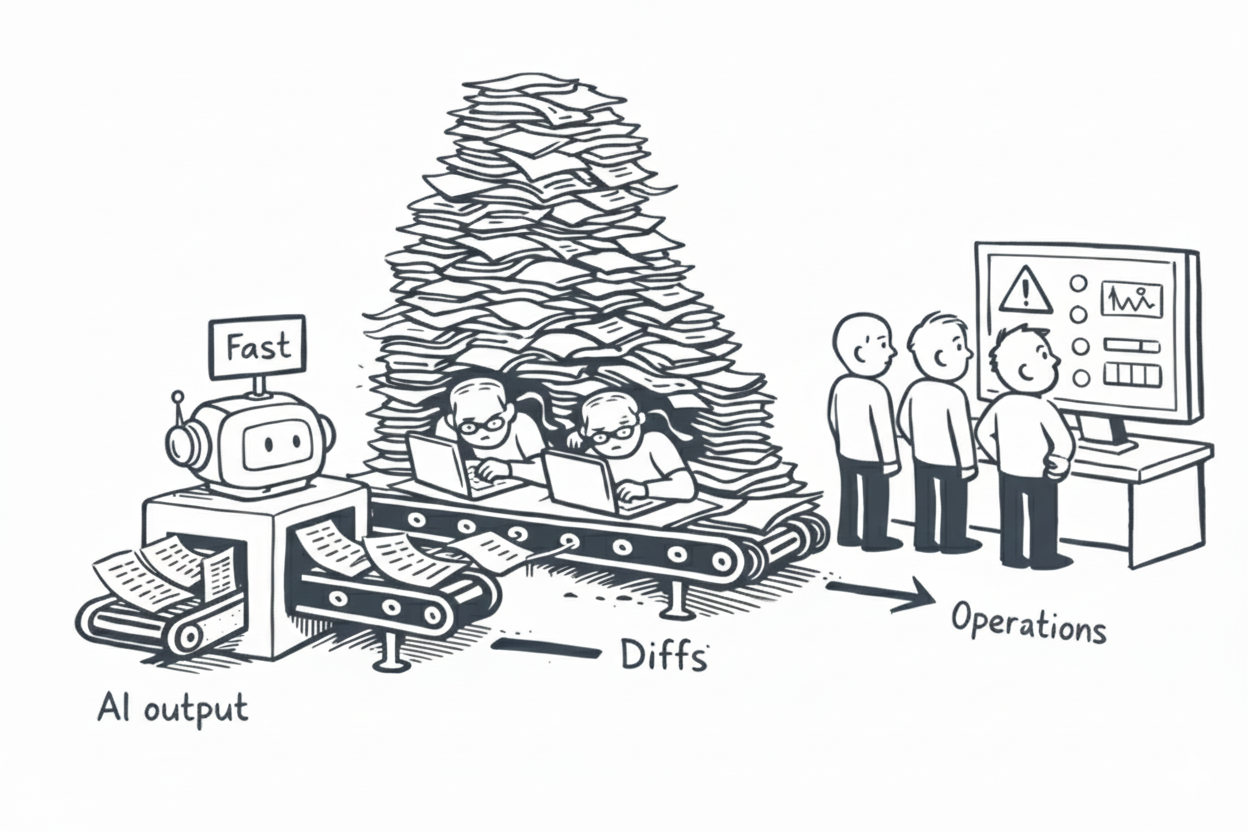

Idea → What/Why (spec) → Draft (AI or human) → Validate (tests/checks) → Review (PR) → Merge

The engineering pipeline doesn’t change. AI just compresses the Draft step, which increases pressure on Spec and Validation.

AI makes exploration cheap and parallel. If you don’t do the normal engineering work (what’s changing, why, what might break, how you’ll know, and how you’ll roll it out), the cost shows up later.

There’s another cost that’s easy to miss: the developer may ship changes without coming away with much understanding of what they just built. That knowledge doesn’t transfer automatically just because the code exists.

This is the shape of what’s now being called epistemic debt: working code with missing understanding, where the bill arrives later when you need to change it, debug it, or defend it in review. I wrote more about it here: Epistemic Debt: the hidden cost of AI speed.

Example 1: One common failure mode is brittle tests: AI can generate “good looking” UI tests from a snapshot of what it sees today, baking in incidental details. They pass once, then become a maintenance trap.

Example 2: Subtle logic drift: the developer steps back, the model decides the shape, and the code can look tidy, pass the wrong tests, and still be wrong.

And yes, it also shows up as larger diffs, slower reviews, fuzzier intent, and a gradual erosion of trust. That is where guardrails become necessary.

The guardrails I rely on

These aren’t rules. They’re the defaults I try to fall back to when the pace goes up and it becomes easy to lose intent. Think of them as team-friendly expectations: the kind of thing you can say out loud in review without it sounding personal.

No explanation, no merge. If the author can’t explain what changed, why it changed, what it assumes, and how it can fail, it shouldn’t ship yet. That’s the simplest way I know to avoid epistemic debt.

Write the intent down before you “improve” the code. For any non-trivial change, we want a tiny written spec somewhere (often just the PR description):

- What behaviour is changing?

- What is explicitly not changing?

- What assumptions does this rely on?

- How did we validate it (tests, checks, manual verification)?

If the model drafts a neat explanation, it’s worth rewriting it in your own words. If you can’t, that’s a signal the change isn’t understood yet.

Keep diffs reviewable. Large diffs collapse multiple decisions into one review moment. If something small turns into something big, it’s usually a sign to split it: isolate refactors from behaviour changes, and isolate scaffolding from logic.

Treat tests as product code. This is where I’ve been bitten. AI generates plausible UI tests from “what the page looks like today”, and they pass once before turning brittle. Aim for tests that assert intent (what must be true), not incidental structure.

If it feels too easy, pause. Switching models, changing behaviour (not just refactoring), touching multiple concerns, or widening scope should trigger a deliberate check-in. If everything feels effortless, it’s worth assuming something important is being skipped and slowing down on purpose.

I’m also thinking about lightweight “guardrails for agents” kept close to the code (a short repo rules file). If it works, it will be because it’s short, specific, and enforced by review and tooling.

How I work right now

Sometimes I code by hand because I want to think. Sometimes I delegate aggressively because I want to think and create in parallel.

Doing this well in a team needs a bit of humour. AI will occasionally do something brilliant, and occasionally do something confidently bizarre. I would rather we can say “that was the model” without embarrassment than pretend none of this is happening. The goal is not secrecy, it is shared habits.

Make AI usage visible, or you can’t manage the risk.

The worst outcome is when people feel they have to hide it. If reviewers don’t know where AI was used heavily, they can’t dial up the right kind of scrutiny (intent, assumptions, tests, and edge cases). Keeping it in the open also lets teams get better together: what prompts worked, what failed, and what guardrails actually helped.

Working with agentic AI looks similar to how I work as a lead developer: I hand off scoped work, review what comes back, and step in to keep the delivery connected, so intent does not get lost as things move faster.

I am definitely not advocating any plan to replace engineers. I am trying to make sure their attention is spent where it pays off most.

What I’m watching next: The systems thinking gap

This model works best for people who already know how to keep a system coherent: what matters, what can break, what to validate, and what to roll back. My biggest question is how a new generation learns that judgement when the act of drafting has become near-instant.

You always had to care what happens after shipping. The difference is you now hit that part much sooner, because code is cheap.

Systems thinking is the habit of asking “what else does this touch?”, other services, data, users, operational load, and failure modes.

Part of that is learning the end-to-end lifecycle of a change. For example: Requirements → Design → Tests → Rollout → Ops

Agentic AI doesn’t remove responsibility; it concentrates it.

Delegation is a senior skill - start teaching it deliberately.

The teams that win won’t just be the ones with the best tools. They’ll be the ones that realise delegation is a senior skill and start teaching it deliberately.

Comments