.NET Performance Tip – Benchmarking

Micro-Benchmarking

Micro-optimising has a bad reputation although I’d argue that knowledge of such things can help you write better code. We should also make the distinction clear between this and micro-benchmarking, on the other hand, which is a little risky but a lot safer if you know how to do it right.

Now, if you’re making that mental link with premature optimization right now, off the back of a 44 year old (mis)quote from Donald Knuth, there are lots of good, more recent and balanced arguments on the subject out there now; and plenty of tools that help you do it better. I think some of the confusion comes from a misunderstanding of where it sits within a much broader range of knowledge and tools for performance. Remember, he did say that ‘we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%’, which sounds about right in my experience.

Common Pitfalls

There’s loads of pitfalls going old-school with System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch such as:

- not enough iterations of operations that take a negligible amount of time

- forgetting to disable compiler optimizations

- inadvertently measuring code not connected to what you are testing

- failing to ‘warm-up’ for account for JIT costs and processor caching

- forgetting to separate setup code from code under test

- and so on…

Enter Adam Sitniks’ BenchmarkDotNet. This deals with all the problems above and more.

BenchmarkDotNet

It’s available as a NuGet package:

And has some excellent documentation:

You have a choice of configuration methods via objects, attributes or fluent. Things you can configure include:

- Compare RyuJIT (default since .NET46 for x64 and since Core 2.0 for x86) and Legacy JIT

- Compare x86 with x64

- Compare Core with full framework (aka Clr)

- JIT inlining (and tail calls, which can be confusingly similar to inlining in 64-bit applications in my experience)

- You can even test the difference between Server GC and Workstation GC from my last tip

A Very Simple Example

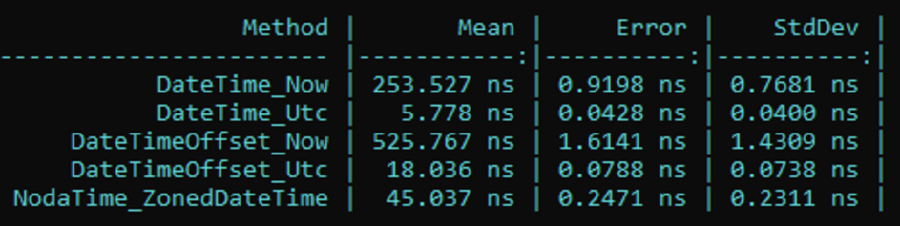

For many scenarios, it is fine to just fire it up with the standard settings. Here’s an example of where I used it to get some comparisons between DateTime, DateTimeOffset and NodaTime.

[ClrJob, CoreJob]: I used the attribute approach to configuration, decorating the class to makeBenchmarkDotNetrun the tests on .NET full framework and also Core.[Benchmark]: used to decorate each method I wanted to benchmark

[ClrJob, CoreJob]

public class DateTimeBenchmark {

private DateTime dateNow;

private DateTimeOffset dateOffset;

private ZonedDateTime nowInIsoUtc;

[Benchmark]

public void DateTime_Now() {

dateNow = DateTime.Now;

}

[Benchmark]

public void DateTime_Utc() {

dateNow = DateTime.UtcNow;

}

[Benchmark]

public void DateTimeOffset_Now() {

dateOffset = DateTimeOffset.Now;

}

[Benchmark]

public void DateTimeOffset_Utc() {

dateOffset = DateTimeOffset.UtcNow;

}

[Benchmark]

public void NodaTime_ZonedDateTime() {

nowInIsoUtc = SystemClock.Instance.GetCurrentInstant().InUtc();

}

}

A call to get things started:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var summary = BenchmarkRunner.Run<DateTimeBenchmark>();

}

Note if you want to try this code, you’ll need to install the NuGet packages for BenchmarkDotNet and NodaTime.

Output:

Obviously, not a substitute for understanding the underlying implementation details of the DateTime class in the Base Class Library (BCL); but a quick and easy to initially identify problem areas. In fact, this was just a small part of a larger explanation I gave to a colleague around ISO 8601, time zones, daylight saving and the pitfalls of DateTime.Now .

One Thing That Caught Me Out

One gotcha is, if you are testing Core and full framework, make sure you create a new Core console application and edit your csproj file, switching out <TargetFramework> for e.g.

TargetFrameworks>netcoreapp2.1;net46</TargetFrameworks>

Comments